EVOLUTIONARY CONSIDERATIONS

Postural schema and movement patterns are interdependent.

Movement enables the ontogenetic (developmental) transformation and adaptation of posture – the transition from infant spinal curves to adult curves exemplifies this interdependence.

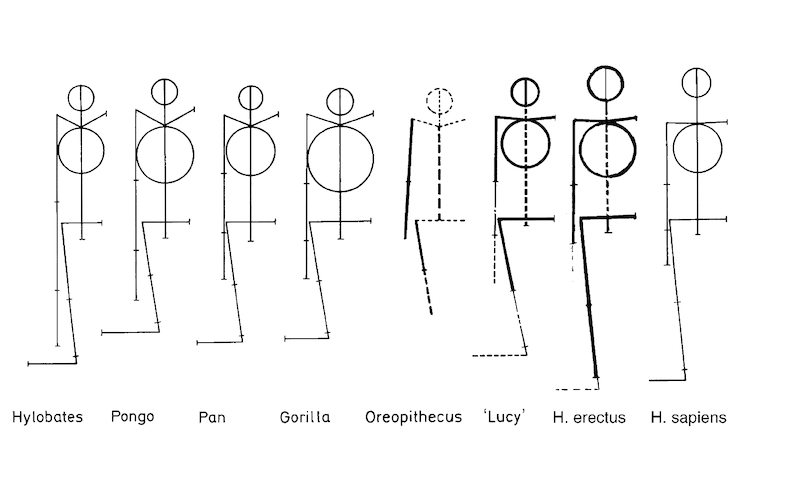

Ontogenetic transformation makes more sense when framed in evolutionary terms. Bipedalism and upright human posture are associated with adaptations of quadrupedal features which have evolved through a lengthy arboreal phase. These adaptations enable energy conservation and load carrying. Current evolutionary thinking suggests that organisms do not adapt to existing niches – instead they find niches for which their morphology is suited.

Quite unlike arboreal apes – hominids do love to wander – and as such our postural traits appear to be primarily related to endurant bipedal walking. However, hominids remain a mosaic of bipedal and quadrupedal features. Quadrupedal muscle activation patterns are unwittingly engaged in many modern sedentary life-work activities.

There is much debate amongst evolutionary biologists about ‘what humans are good for’ – some consensus suggests that we are remarkable generalists with enormous scope for self-generated ontogenesis – skill acquisition plus morphological adaptation to training.

DEVELOPMENTAL

Through growth and development, the infant C-shaped spinal curve transforms into regionally specialised sequences of alternating secondary curves in the lumbar, thoracic and cervical regions.

Development is influenced by much more than genes. The developmental process is an interplay between emergent function, neurological maturation, the material properties of the body and environmental influences. Collectively, this enables the transition from infantile posture to spiralling movement patterns – which employ elastic energy stored in fascia. Fascia materially connects the spine to the extremities through myofascial slings, this arrangement optimises functional movement.

Some embryologists regard fascia as an organ of innerness which creates space and material continuity within the body. Recent theories speculate that fascia is critical to interoception and haptic perception. The development and health of the fascial system has enormous implications for embodiment.

REGIONAL SPINAL BIOMECHANICS

Each region of the spine has distinct biomechanical properties, functions, range of movement and directional preferences.

Sometimes, it can be helpful to think of the spine in regional terms but it is perhaps more important to recognise the continuity of the spine – from coccyx to cranium.

This continuity encompasses fascia, superficial and deep ligaments, joint capsules and dural membranes. Material continuity underpins the non-linear properties of the spine and entire musculoskeletal system.

CULTURAL-AESTHETIC

Deportment and good posture are in the main cultural artefacts. Highly divergent and contradictory ideals, of good and bad posture, exist within different (sub)cultural contexts.

The process of enculturation (e.g. military service) creates postural norms, ideals or caricatures. Posture can also be employed to communicate a specific message or aesthetic.

EMOTIONAL-PSYCHOLOGICAL-PATHOLOGICAL-INERTIAL

Posture is an expression of and is influenced by the interactions of numerous factors including:

– transient and sustained affective states

– wellbeing, health, injury, illness and pathology

– motion & movement, disuse, gravity, overload and overuse

All of these influences can become inscribed into the fabric of the body as well as trigger and perpetuate poor neuromuscular patterns through a mixture of static (inertia) and dynamic forces.

FEATURED IMAGE:

H. Preuschoft. Mechanisms for the acquisition of habitual bipedality: are there biomechanical reasons for the acquisition of upright bipedal posture (2004).